IB Syllabus focus:

'Detailed account of the events leading to the invasion of Manchuria in 1931.

The progression of Japanese forces into northern China.

International and local reactions to the invasion.'

The 1931 invasion of Manchuria by Japan heralded a transformation in East Asia's balance of power, reflecting Japan's ambition to dominate the region.

Events Leading to the Invasion of Manchuria

Economic Pressures

Industrialisation and Resource Needs: As Japan underwent rapid industrialisation in the early 20th century, its dependency on imported resources grew, especially raw materials like iron and coal.

Depression and Overseas Markets: The global economic downturn affected Japan's exports severely. By 1931, the Great Depression had intensified the country's need to secure overseas markets and resources.

Kwantung Army's Role

Semi-Autonomy: Stationed in the Kwantung Leased Territory, this elite Japanese unit operated with significant autonomy, often bypassing official channels and directives from Tokyo.

Expansionist Ambitions: The Kwantung Army's top brass harboured strong nationalist and expansionist sentiments, pushing for greater territorial acquisition.

The Mukden Incident

Prelude to Invasion: On 18th September 1931, an explosion near Mukden damaged a segment of the South Manchuria Railway. This 'act of sabotage' was swiftly blamed on Chinese nationalists.

Kwantung Army's Agenda: Investigations later revealed that the incident was staged by the Kwantung Army itself, seeking a casus belli for military expansion.

Japanese Progression into Northern China

Swift Occupation

Seizing Key Cities: Capitalising on the pretext of the Mukden Incident, Japanese troops rapidly advanced, capturing major cities, including Mukden, Changchun, and Harbin.

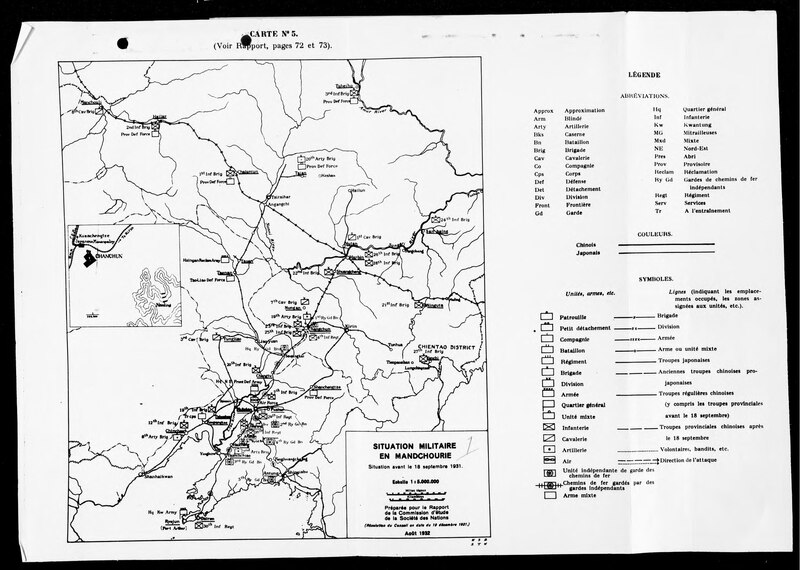

Map of Manchuria showing the military situation during 1931–1932, including the South Manchuria Railway, principal cities, and lines of Japanese advance that led to the swift occupation of the region. Labels allow students to locate Mukden (Shenyang), Changchun, and Harbin mentioned in the text. Source

Formation of Manchukuo: By early 1932, Japan declared the establishment of Manchukuo, installing Puyi, the last Qing emperor, as its puppet ruler.

Puyi during the Manchukuo period, presented in full dress to project legitimacy for the Japanese-backed state. The portrait helps contextualize Japan’s use of a familiar imperial figurehead to consolidate authority after the occupation. Source

Pushing Beyond Boundaries

Inching Towards Beijing: With Manchuria secured, the Japanese set their sights on northern China. Major cities, such as Beijing and Tianjin, were occupied by 1933.

Skirmishes and Standoffs: As they moved south, Japanese forces encountered stiff resistance. Notably, at the Great Wall, Chinese troops put up a spirited defence before the Tanggu Truce formalised a demilitarised zone.

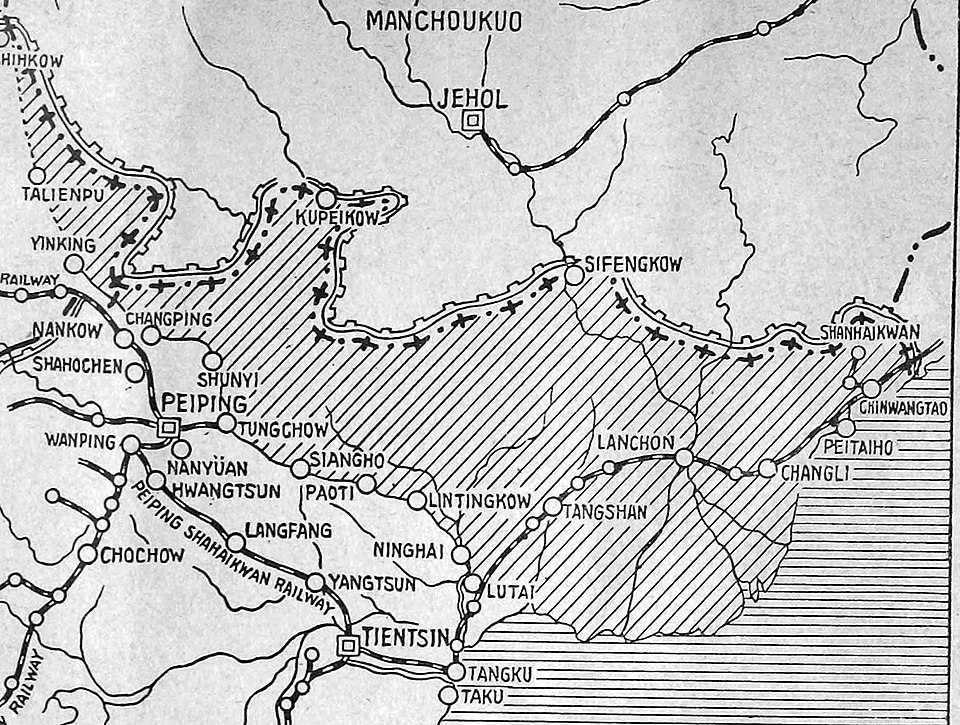

Demilitarized zone established by the Tanggu Truce in 1933, which limited Chinese Nationalist deployments in northern China and facilitated Japan’s security perimeter south of Manchuria. Source

International and Local Reactions to the Invasion

Chinese Backlash

Guerilla Warfare: With a weak central authority, many Chinese regions responded with grassroots resistance. Guerilla fighters frequently harassed Japanese supply lines and carried out sabotage missions.

Nationalistic Outpouring: The invasion spurred a renewed sense of Chinese nationalism. Mass protests, rallies, and boycotts of Japanese goods occurred throughout China.

International Community's Stance

Lytton Commission: Dispatched by the League of Nations, the Lytton Commission conducted an on-ground assessment. Their 1932 report criticised Japan's actions, but the League's response was largely symbolic.

Reluctance to Intervene: Western powers, grappling with economic crises and wary of military confrontations, voiced disapproval but were hesitant to take tangible actions against Japan.

Japan's Counterarguments

Stabilising Influence: Japan framed its invasion as a mission to bring order to a region rife with banditry and instability.

Pan-Asian Rhetoric: Couched in terms of liberating Asia from Western imperialism, Japan's "Asia for Asians" slogan sought to justify its territorial ambitions.

Economic Repercussions

Trading with Manchukuo: Some countries, sensing economic opportunities, engaged in trade with Manchukuo despite its dubious international standing.

Ineffective Sanctions: While calls for economic sanctions against Japan grew louder, the actual measures implemented were patchy and lacked the coordination required to deter Japan.

The Broader Context: Imperial Ambitions

Asia as a Battleground: Japan's invasion wasn't an isolated incident. It was a part of a broader pattern where major powers sought to reshape Asia in line with their strategic interests.

Ideological Drives: Japan's foray into Manchuria was as much about resources as it was about asserting a new vision for Asia, one where Japan assumed a leadership role.

Note: Japan's manoeuvres in Manchuria set the stage for further territorial ambitions, leading the country down a path of increasing militarism and, eventually, confrontation with global powers.

FAQ

The South Manchuria Railway (SMR) was of paramount significance to Japanese interests in Manchuria. Built after the Russo-Japanese War, SMR facilitated Japan's economic penetration into Manchuria, allowing the transport of goods, troops, and resources. Its importance can be gleaned from the fact that the Mukden Incident, which precipitated the invasion, revolved around an alleged act of sabotage on this railway line. The incident gave Japan the pretext it needed to launch a full-scale invasion. Throughout the occupation, the railway remained a lifeline, serving military, economic, and administrative functions, reflecting Japan's intertwined strategic and economic goals in the region.

The Tanggu Truce, signed in 1933, was an agreement between China and Japan following intense hostilities. The truce established a demilitarised zone south of the Great Wall, with Chinese forces withdrawing from this area. This truce significantly impacted Japan's progression as it essentially legitimised the territorial gains Japan had made up to that point. Additionally, the demilitarised zone created a buffer, reducing the likelihood of direct confrontations and allowing Japan to consolidate its control over occupied territories. However, it also indicated that Japan's southward push had met significant resistance, suggesting the challenges Japan would face in any further attempts at expansion.

Yes, there were dissenters within Japan who criticised the invasion of Manchuria. Some of these critics were found within the government and military, who believed that the Kwantung Army acted too independently and rashly, potentially dragging Japan into unwanted conflicts. Additionally, liberal intellectuals, journalists, and some politicians decried the invasion as an act of unchecked militarism, voicing concerns about its ramifications on Japan's international standing. However, these voices of dissent were often overshadowed by fervent nationalism, aggressive propaganda, and, in some cases, suppressed by the government, especially as Japan continued down the path of militarism and imperial expansion.

The Kwantung Leased Territory was a concession leased to Japan by the Qing Dynasty of China after the Russo-Japanese War in 1905. Located in southern Manchuria, it included the Liaodong Peninsula and the railways associated with it. Its significance lies in its strategic and economic value to Japan. The region offered Japan a foothold on the Asian mainland, allowing it to project power and influence over Manchuria and Northern China. Economically, the territory was valuable due to its rich resources and the South Manchuria Railway, which facilitated Japan's trade and transport. Additionally, the semi-autonomous Kwantung Army stationed there played a pivotal role in Japan's aggressive expansion in the 1930s.

Puyi was the last emperor of the Qing Dynasty in China, ascending to the throne as a child in 1908 and later abdicating in 1912 following the Xinhai Revolution. Japan's installation of Puyi as the ruler of Manchukuo served multiple purposes. Firstly, it provided a veneer of legitimacy to the puppet state of Manchukuo, given Puyi's royal lineage. Secondly, Puyi's status as a former emperor symbolised a continuity of leadership, implying that Manchukuo was not just a mere creation of Japan but had historical significance. Finally, having a puppet ruler made it easier for Japan to control and administer Manchukuo without overtly appearing as an occupying force, thus making their occupation more palatable to both international observers and local inhabitants.

Practice Questions

The Mukden Incident, orchestrated by the Kwantung Army in 1931, was undeniably crucial in facilitating Japan's invasion of Manchuria. Acting as a catalyst, this false-flag operation provided Japan with a justifiable pretext to pursue its expansionist ambitions. While there were underlying economic and strategic reasons, like resource acquisition and countering the perceived Chinese threat, the Mukden Incident offered an immediate cause and rallied Japanese military support. In essence, while Japan might have eventually sought reasons to invade due to pre-existing motivations, the Mukden Incident expedited and legitimised this action in the eyes of the Japanese leadership.

The international response to Japan's invasion of Manchuria was characterised by symbolic condemnations but a tangible lack of decisive action. This mirrored the geopolitical climate of the early 1930s, where Western powers, grappling with the aftershocks of the Great Depression, prioritised domestic challenges over foreign confrontations. The League of Nations, though critical of Japan, was ineffectual in implementing penalties, underscoring its inherent weaknesses. Additionally, the reluctance of global powers to militarily or economically confront Japan reflected a broader desire to avoid conflict, even if it meant acquiescing to clear acts of aggression. In summary, the global response was shaped by economic turmoil, an aversion to conflict, and the limitations of international institutions.