IB Syllabus focus:

'The political ambitions and economic aspirations driving Spanish exploration.

The role of religious doctrine in justifying conquest.

The personal motives of key figures involved in the expeditions.'

In the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the Spanish crown, driven by a blend of political ambition, economic desires, and religious fervour, embarked on the exploration and subsequent conquest of the New World. Understanding these factors is crucial to grasping the dynamics of the period.

Political Ambitions Driving Spanish Exploration

Spain in the late 15th century was emerging from a turbulent period. With the Reconquista culminating in the capture of Granada in 1492, Spain sought to consolidate its newfound unity through exploration. For more context on this era, see Motives for Exploration in the 15th Century.

Consolidation of Power:

Spain's unity under Ferdinand and Isabella was relatively fresh. Establishing a strong overseas empire became an avenue to solidify their rule and the sense of a unified Spanish identity.

A successful conquest would elevate Spain's status among European nations, marking it as a formidable global power.

Rivalry with Portugal:

The Iberian neighbours were intense competitors on the seas. With Portugal's early gains in the exploration race, Spain felt the pressure.

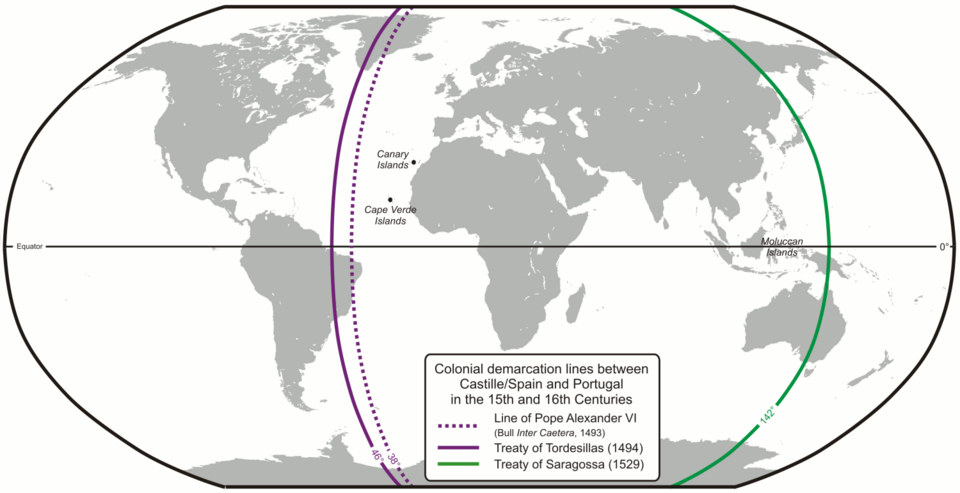

The Treaty of Tordesillas only intensified this competition. By dividing the New World, it gave Spain the impetus to explore aggressively, ensuring they staked a claim before Portugal could encroach on their domain.

This map shows the papal and diplomatic “lines of demarcation” that divided Atlantic (1494, Tordesillas) and Pacific (1529, Saragossa) spheres between Castile/Spain and Portugal, illustrating how geopolitical rivalry structured early expansion. Labels make clear which zones fell into each crown’s orbit. It includes the later Saragossa line, which is additional context beyond the immediate syllabus focus. Source

Expansion of Territory:

More territories meant more resources and more power. By controlling vast portions of the Americas, Spain could exert its influence and establish a foothold in the global geopolitical landscape.

Economic Aspirations Behind the Conquests

The allure of unimaginable wealth was a predominant driving force. Tales of cities laden with gold and other riches stoked the fires of imagination and greed. To understand the broader economic impact, refer to The Spanish Colonial System in the Philippines.

Wealth of the Indies:

The prospect of gold, silver, and precious gems in the New World was irresistible. This potential wealth was a primary motivator for both the crown and the individual conquistadors.

Reports from initial explorations, sometimes exaggerated, painted a picture of a land brimming with untapped resources, waiting for the Spanish to exploit.

Trade and Commercial Interests:

Spain sought to dominate global trade routes. With Asia's rich markets, establishing a direct route was of paramount importance, eliminating the need for middlemen and increasing profits.

New territories meant new goods: crops like tobacco, maize, and cocoa became valuable commodities in the European market.

This world map traces principal sixteenth-century Portuguese (blue) and Spanish (white) sea lanes, including the Manila–Acapulco galleon that integrated American silver and Asian markets. It visualizes how control of routes underpinned imperial wealth and policy. Source

Land Ownership and the Encomienda System:

The system allowed conquistadors to be rewarded with land and native labour. The vast territories and their indigenous populations, thus, became sources of substantial personal wealth and power for these explorers.

Role of Religious Doctrine in Justifying Conquest

Religious motivations were intertwined with the other reasons for exploration and conquest. The Catholic Church and individual Spaniards saw the New World as a ripe field for evangelism. The importance of religious patronage during this period is further discussed in The Importance of Patronage in the Renaissance.

Evangelisation and Conversion:

The idea of saving souls was genuine for many. The belief that they were bringing the 'true faith' to the 'heathens' provided moral justification for many of the atrocities committed during the conquest.

Converting the indigenous population would also make them more amenable to Spanish rule, making governance easier.

Papal Support:

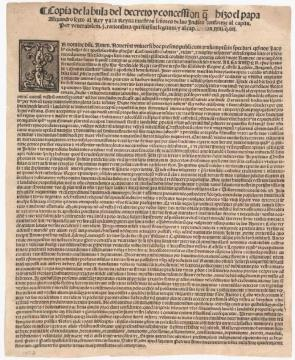

The Catholic Church, keen on expanding its influence, supported Spain's overseas ambitions. The Papal Bull, for instance, provided religious justification for the Spanish claim over vast territories.

By converting the natives, Spain also aimed to strengthen Catholicism against rising Protestant movements in Europe.

Primary-source scan of Inter caetera (May 4, 1493), in which Pope Alexander VI authorizes Spanish claims beyond a westward demarcation line and urges evangelization of non-Christian peoples. The document exemplifies how religious authority underwrote political and economic aims. Source

Religious Zeal of Conquistadors:

Not all explorers were devoutly religious, but many did believe in their divine mandate. They saw themselves as soldiers of Christ, bringing salvation to the New World, even if it was by the sword.

Personal Motives of Key Figures in the Expeditions

While overarching themes of politics, economics, and religion played significant roles, individual motivations of key players were equally pivotal. Individual ambitions often mirrored broader societal changes, such as those seen during events like the French Revolution: Monarchy to Republic.

Hernán Cortés:

Born to a lesser noble family, Cortés sought to make a name for himself. The conquest of the Aztec Empire, with its immense wealth, was his path to glory and riches.

His letters to Charles V highlight his ambitions, asserting his loyalty to the crown but also subtly demanding recognition for his feats.

Christopher Columbus:

His motivations were multifaceted. Along with seeking a route to Asia's riches, he harboured ambitions of evangelising the East. His religious fervour is evident in his writings.

Columbus, too, sought personal glory, hoping to elevate his status and secure a legacy.

Francisco Pizarro:

Much like Cortés, Pizarro came from a humble background. The Incan Empire, with stories of its golden palaces, became his target.

His ambition was evident in his persistence. Even after multiple failed expeditions, he pressed on, driven by the promise of wealth and the allure of the unknown.

Other Explorers and Conquistadors:

Beyond the well-known figures, countless others were drawn to the New World. Whether it was the allure of noble titles, vast lands, or simply the thrill of adventure, each had personal motivations driving their journey into the unknown.

As the Spanish galleons set sail towards the Americas, they carried with them a mix of ambition, greed, and zeal. This potent combination would shape the fate of two continents, marking the beginning of a new chapter in world history. For further insights into related historical contexts, explore the Boxer Rebellion and Late Qing Reforms.

FAQ

Spain's domestic situation played a pivotal role in shaping its overseas ambitions. The completion of the Reconquista in 1492, with the fall of Granada, signalled the end of nearly 800 years of Muslim rule in parts of the Iberian Peninsula. This victory fostered a strong sense of Christian identity and unity. The newly unified Spain, under the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, sought to channel this momentum into overseas ventures. The desire to consolidate power, fortify the newly established sense of Spanish national identity, and to compete with neighbouring Portugal on the global stage meant that overseas exploration and conquest became not just an ambition but a necessity.

Spain introduced the 'encomienda' system in the Americas, a feudal-like system that granted Spanish settlers or 'encomenderos' the right to extract labour and tribute from native populations in specific territories. In return, these encomenderos were expected to provide protection to the natives and convert them to Christianity. However, in practice, this system often led to severe exploitation, with natives being subjected to brutal work conditions, especially in mines. The 'encomienda' system was ostensibly introduced to protect and evangelise the indigenous populations, but it mainly served as a mechanism for Spain to harness the New World's vast resources efficiently.

Indigenous alliances were crucial for the Spanish, especially given the relatively small number of conquistadors compared to the vast native populations. In the case of Cortés and the Aztecs, alliances with local tribes were instrumental. Many of these tribes, like the Tlaxcalans, had grievances against the dominant Aztecs due to their oppressive policies and demands for tributes. Cortés astutely leveraged these animosities, forging alliances that provided him with thousands of additional warriors, intelligence, and logistical support. These alliances not only bolstered his military capabilities but also lent legitimacy to his campaign against the Aztecs, making it appear less as a foreign invasion and more as a collective uprising against Aztec dominance.

The Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in 1494, was a pivotal agreement between Spain and Portugal, ratified by the Pope. It essentially divided the unexplored world into two spheres of influence: Spain gained rights to lands west of the demarcation line, and Portugal to lands east. For Spain, this treaty legitimised their claim to vast swathes of the Americas, ensuring that their primary European competitor, Portugal, would not challenge their conquests. It gave Spain the confidence to invest heavily in exploration and settlement of the New World, knowing that any discoveries and established colonies in the stipulated territories would remain unchallenged by their Iberian neighbour.

Yes, not everyone in Spain supported the conquests unequivocally. One of the most vocal critics was Bartolomé de las Casas, a Spanish Dominican friar. He was horrified by the treatment of indigenous people by the conquistadors. Initially granted an encomienda himself, he renounced it after witnessing the atrocities committed against the natives. In his writings, especially "A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies", he detailed the abuses and argued fervently against the mistreatment and enslavement of the indigenous population. He advocated for the humane treatment of the natives, arguing that they were rational beings with rights, challenging the prevailing viewpoint that they were inferior and could be treated as mere property.

Practice Questions

Religious motives were integral to Spain's exploration and conquest in the 16th century. While economic aspirations and political ambitions were undoubtedly influential, religion provided the moral and ethical framework underpinning many of these expeditions. The Catholic Church, through instruments like the Papal Bull, gave a divine mandate for the conquest, seeing the New World as a vast expanse ready for evangelism. Furthermore, the idea of "saving souls" offered moral justification, even when faced with the atrocities of conquest. Additionally, the rise of Protestantism in Europe meant the spread of Catholicism in new territories was also a strategic move. Thus, religion was not just a passive backdrop but a proactive force driving Spanish imperial ambitions.

Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro, driven by personal ambitions rooted in their humble origins, significantly impacted the trajectory of Spanish exploration. Cortés, keen on etching his name in history, embarked on the audacious conquest of the Aztec Empire. His determination and tactics, alongside his desire for personal enrichment and recognition, culminated in the fall of a great empire. Similarly, Pizarro, lured by tales of the Incan Empire's riches, exhibited tenacity in his repeated attempts to conquer it. His unyielding spirit, stemming from a desire for wealth and status elevation, led to the eventual fall of the Incas. In both cases, personal motives directly influenced the strategies employed and the outcomes achieved, demonstrating the profound impact of individual agency on historical events.