IB Syllabus focus:

'The influence of the Catholic Church in political affairs and the drive towards a unified Christian Spain.

The role of religion in shaping public opinion and policy decisions.

Specific political objectives of key figures and how these aligned with broader religious motives.'

In late 15th-century Spain, the trajectory of political decisions was profoundly influenced by religious motivations. A landscape rife with the culmination of the Reconquista, the period bore witness to the marriage of political ambitions with religious fervour.

Influence of the Catholic Church in Political Affairs

The Catholic Church's footprint on Spain's political sphere was colossal. Its influence seeped into various aspects of governance and policy-making:

Advisory Capacity

Royal Courts: Church officials were often consulted on matters of governance, providing spiritual guidance intertwined with political insight.

Religious Endorsement: Royal decisions, especially those involving warfare or territorial expansion, often sought the Church's blessing, lending them a divine legitimacy.

Economic Power

Landholdings: Vast tracts of fertile land were owned by the Church, making it a significant economic player. This economic clout provided the Church a firm footing in political circles.

Tithes and Donations: The Church's coffers swelled with regular tithes and hefty donations, further amplifying its influence in political matters.

Diplomatic Channels

Inter-Kingdom Mediation: The Church often played the role of mediator, resolving disputes between Christian kingdoms.

Foreign Relations: The Church also influenced Spain's relations with other European kingdoms, ensuring the country's decisions aligned with the broader interests of Christendom.

Drive for Unification

Reconquista Support: The Church fervently backed the mission to reclaim Spain from Muslim rule, painting the Reconquista as a holy endeavour.

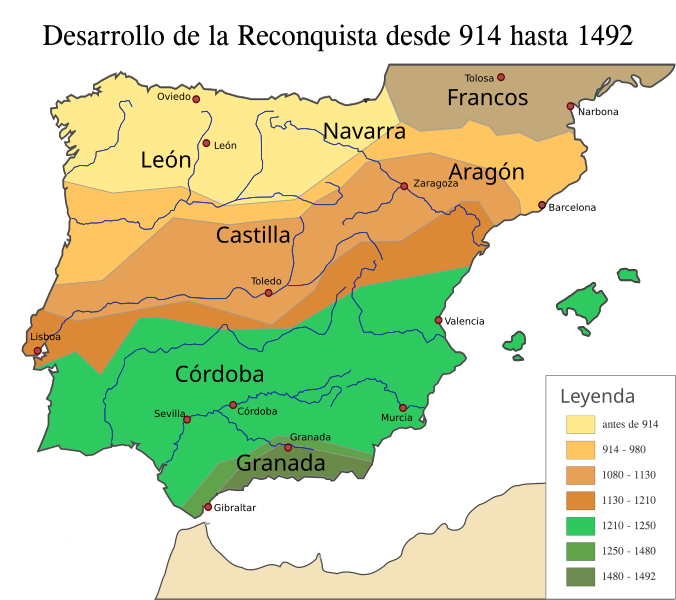

This map traces the territorial advance of Christian polities in Iberia culminating in 1492, situating the Reconquista as a long-running, Church-endorsed campaign that fused piety with policy. It clarifies Granada’s position as the final Muslim stronghold and why its fall carried powerful religious symbolism. Source

Spiritual Mobilisation: Using religious imagery and rhetoric, the Church mobilised vast segments of the populace in support of the Reconquista.

Religion’s Role in Shaping Public Opinion

Religion permeated every facet of daily life, profoundly moulding public sentiment:

Moral Authority

Voice of God: Church declarations and proclamations were deemed divine, carrying unparalleled weight in swaying public opinion.

Canon Law: The Church's religious laws were sometimes even more influential than the kingdom's own legal codes.

Sermons and Propaganda

Political Messaging: Sermons, while primarily spiritual, were strategically utilised to convey political messages, particularly during times of conflict.

Religious Festivals: Festivals and religious observances became occasions for political rallying, reinforcing the union of religious and political objectives.

Educational Influence

Curriculum Control: With the Church overseeing most educational institutions, it was uniquely positioned to inculcate a fusion of religious and political loyalty in students.

Scholarships: Promising students were often granted church-funded scholarships, ensuring that the next generation of leaders was moulded by Church ideologies.

Political Objectives and Alignment with Religious Motives

Key political figures of this era seamlessly interwove their political goals with overarching religious motivations:

Fernando de Aragón and Isabel de Castilla

Religious Foundation: Their profound Catholic faith anchored their governance, perceiving Spain's unification under Christianity as a divine command.

Joint Rule: Their marriage united Castile and Aragon, creating a formidable Christian force. Together, they embarked on the final push against Muslim-ruled Granada, framing it as a holy war.

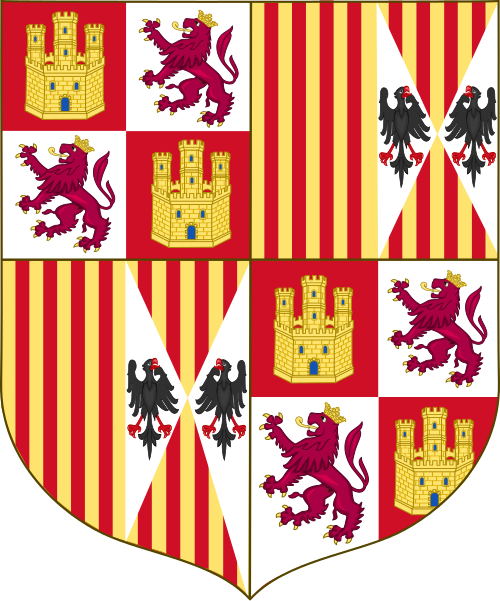

The composite arms of the Catholic Monarchs combine the emblems of Castile and Aragon to signal dynastic union and a shared Christian mission. As a state symbol, it illustrates how rulership and religion were publicly fused in the late fifteenth century. Source

Tomás de Torquemada

Faith-driven Zeal: A Dominican friar, Torquemada's unwavering commitment to purifying Spain's religious landscape drove his decisions.

Spanish Inquisition: Torquemada's influence was instrumental in establishing the Spanish Inquisition. Under his guidance, the Inquisition sought to eliminate perceived heresies, aligning with both religious purification and political consolidation.

Abu Abdallah (Muhammad XII)

Religious Protectorate: As Granada's last Muslim ruler, he fervently worked to shield his subjects from Christian conversion pressures.

Diplomacy over Warfare: Recognising the Christian kingdoms' might, he veered towards diplomatic solutions to maintain Granada's sovereignty. His reign's culmination, marked by Granada's surrender, was both a political and religious turning point.

To comprehend Spain's tumultuous 15th century is to understand the intricate dance between religion and politics. The era's defining events, from the Reconquista's climax to the Spanish Inquisition's genesis, are testaments to this inseparable bond. The legacies of the era's luminary figures, each propelled by a blend of faith and ambition, underscore this union's profundity.

FAQ

The majority of the Spanish populace in the 15th century, being devoutly Catholic, generally supported the fusion of religion and politics. The Church's portrayal of the Reconquista as a holy war resonated deeply, galvanising many to either actively participate or offer support. Furthermore, the Church's influence in education meant that successive generations grew up viewing this amalgamation as the norm. However, it's essential to note that Spain was diverse. Minority groups, especially Jews and Muslims, often faced the harsher side of these policies, leading to feelings of alienation, forced conversions, or the eventual choice of exile.

Certainly, while figures like Fernando, Isabel, and Torquemada are well-known, several lesser-known individuals played crucial roles driven by their religious motivations. Cardinal Mendoza, for instance, was not only a religious leader but also a trusted advisor to the monarchs, playing a key role in the conquest of Granada. Similarly, Queen Isabel’s confessor, Hernando de Talavera, sought peaceful conversions of Muslims post the Granada conquest, highlighting a more compassionate approach grounded in faith. These figures, among others, were instrumental in shaping the religious and political landscape of 15th-century Spain.

Spain's melding of religion and politics significantly influenced its foreign relations during the 15th century. The shared Catholic faith became a cornerstone of alliances, especially with other Christian kingdoms, fostering a united front against perceived external threats, such as the Ottoman Empire. Diplomatic missions often had religious personnel accompanying or even leading them, ensuring that political negotiations had a religious undertone. Moreover, Spain's commitment to the Reconquista and the subsequent expulsion of Jews and Muslims sometimes put it at odds with regions that harboured or supported these expelled communities.

Throughout the Reconquista, the Catholic Church masterfully utilised religious imagery and rhetoric to rally support. Religious leaders equated the reconquest of Iberia with the biblical stories of the chosen people reclaiming their promised land. This portrayed the struggle against Muslim rule as divinely sanctioned. The Church also frequently invoked the Virgin Mary as a patroness of the Reconquista, suggesting that she watched over and guided the Christian warriors. Moreover, many battles and campaigns were preceded by religious processions, blessings, and the presentation of holy relics, cementing the belief that the military endeavours were under divine patronage and guidance.

The Catholic Church's economic clout in 15th-century Spain was considerable, stemming primarily from vast landholdings. These tracts of land made the Church one of the major landlords, ensuring its say in agrarian policies and regional matters. Additionally, tithes—a tenth of one's earnings given to the Church—and generous donations from the nobility filled its coffers. This wealth allowed the Church to sponsor ventures, including military campaigns, and back the crown financially in times of need. Furthermore, their economic might meant that the Church could affect trade decisions, push for certain economic policies, and hold sway over influential aristocrats and merchants, thereby indirectly influencing political decisions.

Practice Questions

In late 15th-century Spain, religious motivations and political ambitions were deeply intertwined, particularly evident in the decisions of prominent figures. Fernando de Aragón and Isabel de Castilla exemplify this, as their devout Catholic faith buttressed their objective of a unified Christian Spain. Their joint conquest of Granada was framed both as a political strategy and a divine command. Similarly, Tomás de Torquemada's religious zeal as a Dominican friar led to the Spanish Inquisition's establishment, aiming for both religious purification and political consolidation. Furthermore, Abu Abdallah’s efforts to maintain Granada's Muslim sovereignty against Christian forces underscore the melding of religious protection with political strategy.

The Catholic Church played a pivotal role in moulding 15th-century Spain's political terrain. Beyond its spiritual realm, the Church held significant economic power through its landholdings and tithes, thereby exerting influence on political decisions. The Church's advisory capacity in royal courts infused governance with religious perspectives, ensuring that political manoeuvres often had the Church's endorsement. Moreover, the Church’s enthusiastic support for the Reconquista, framing it as a holy endeavour, showcased its influence in steering political campaigns. Additionally, through control over education, the Church could further ingrain its perspective into the populace, reinforcing the union of religious ideologies with political loyalties.