IB Syllabus focus:

'Discuss collaboration between leaders like Lewanika and Khama with the British colonial powers and the reasons for their collaboration.'

In the context of European imperialism in Africa, the strategies adopted by African leaders to either resist or collaborate with the imperial powers varied significantly. The cases of King Lewanika of Barotseland and King Khama III of Bechuanaland are exemplary for understanding the intricacies of collaboration with the British during this era.

King Lewanika of Barotseland

King Lewanika’s rule (1878–1916) is characterised by his diplomatic engagements with British colonialists, navigating the pressures of imperialism with the goal of safeguarding Barotseland’s autonomy.

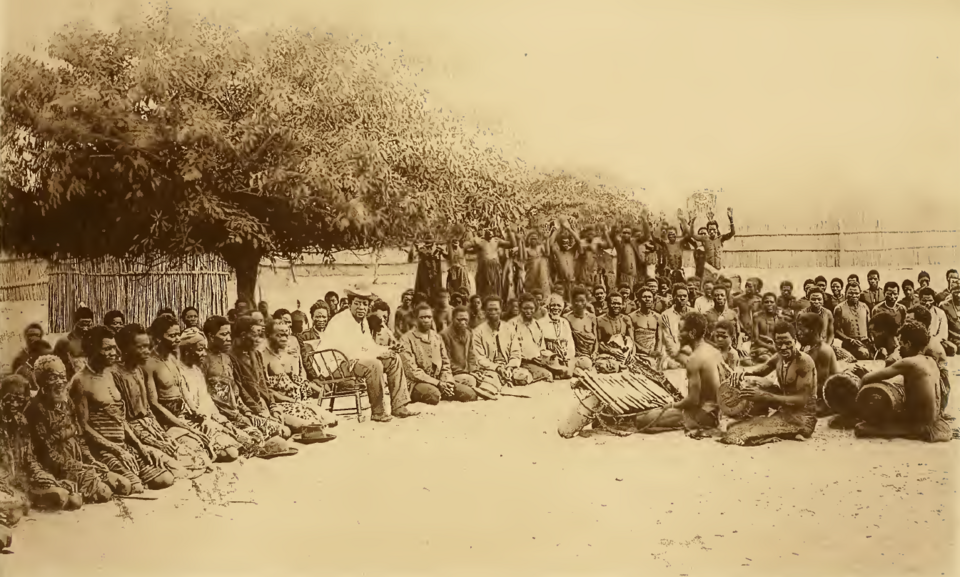

Lewanika presides over his court in Barotseland in the early 1890s, illustrating the institutions and legitimacy he sought to protect through British protection treaties. The scene underscores why a ruler might pursue collaboration to preserve internal sovereignty amid regional threats. Source

Strategic Collaboration

Fear of Annexation: Lewanika sought an alliance with the British as a buffer against Portuguese and Boer incursions, who were expanding their territories in Southern Africa.

Modernisation Ambitions: He aspired to leverage European technology and education to advance his kingdom.

Military Aid: In exchange for mineral rights, Lewanika was promised military assistance against domestic and external threats.

Missionary Influence: Missionaries played a pivotal role, convincing Lewanika of the benefits of British protection and Western education.

Consequences of Collaboration

Misplaced Trust in Treaties: The Lochner Concession of 1890, which Lewanika believed was a business agreement, was misrepresented by Cecil Rhodes' British South Africa Company as a protectorate treaty.

Resistance to Exploitation: When the BSAC began to exploit Barotseland, Lewanika protested to British authorities, albeit with limited success.

Legacy of Sovereignty: Despite the challenges, Lewanika's kingdom retained a higher degree of autonomy compared to other regions under direct colonial rule.

King Khama III of Bechuanaland

Khama III is often lauded for his diplomatic prowess and foresight in dealings with the British, which allowed Bechuanaland to retain significant self-governance.

Pragmatic Collaboration

Defence Against the Boers: Recognising the threat posed by the South African Republic (Transvaal), Khama approached the British for protection, who were equally keen on curtailing Boer expansion.

Modernisation and Christianity: Khama embraced Christianity and Western education, aligning his kingdom’s interests with British cultural values.

Protection of Cultural Integrity: Collaboration was seen as a way to maintain the Bechuana way of life against disruptive external influences.

Collaboration Outcomes

Autonomy in Governance: Khama managed to maintain control over local governance, keeping the colonial administration at arm’s length.

Land Rights: Persistent negotiations ensured that Bechuanaland reserved lands for the Tswana people, a move to counter land seizures common in other colonised areas.

Alliance in Conflict: Khama’s troops supported the British in regional conflicts, solidifying his kingdom’s status as a valuable ally.

Comparative Analysis of Lewanika and Khama's Strategies

Diplomatic Approaches

Proactive Diplomacy: Khama’s successful trip to England in 1895 to advocate for his kingdom’s interests contrasted with Lewanika’s reliance on less effective treaty negotiations.

Long-term Outcomes: Khama’s direct engagement with the British Crown resulted in the establishment of the Bechuanaland Protectorate, which arguably preserved more autonomy than Lewanika’s Barotseland under BSAC’s indirect rule.

Preservation of Kingdoms

Degree of Sovereignty: Both leaders managed to preserve a semblance of sovereignty, with Lewanika’s kingdom being absorbed into Northern Rhodesia and Khama’s Bechuanaland remaining a protectorate.

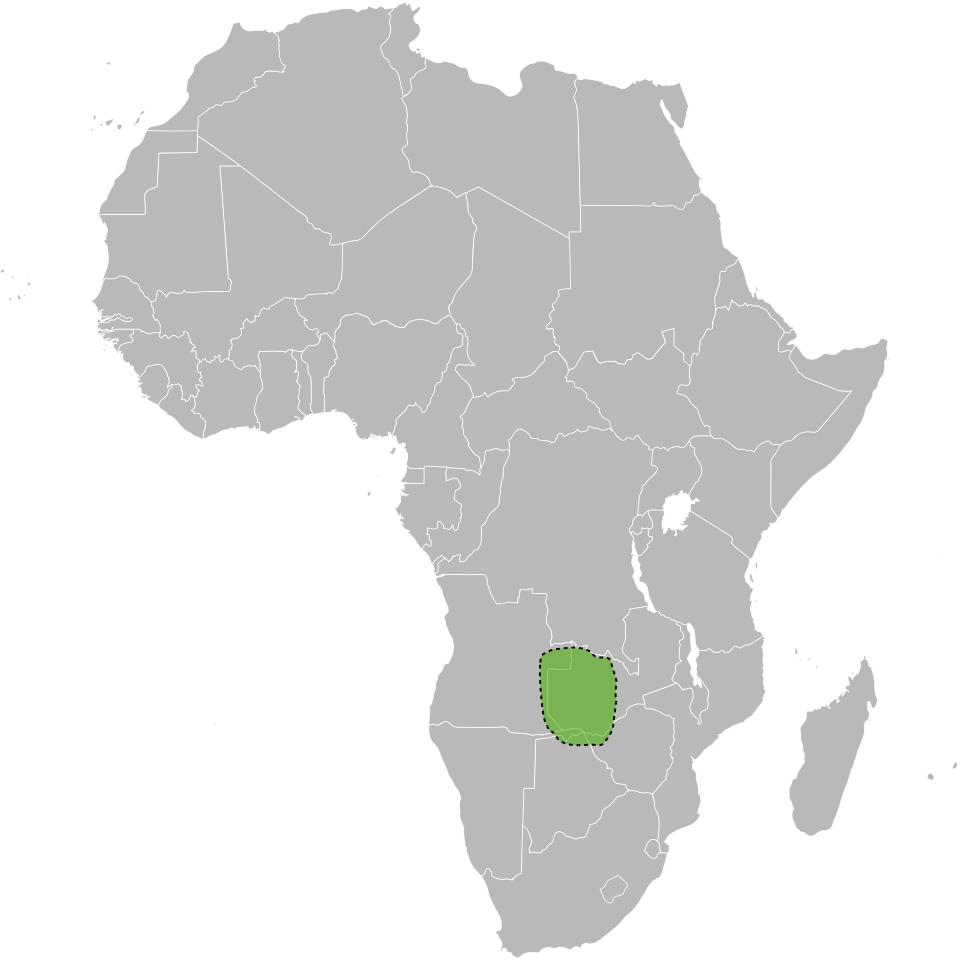

Locator map showing the approximate extent of Barotseland, homeland of the Lozi (Barotse). Use this to orient students when comparing Barotseland’s trajectory with Bechuanaland’s under British rule; note that colonial borders (e.g., Northern Rhodesia) are not shown. Source

Cultural Preservation: Lewanika and Khama prioritised the preservation of their respective cultures and social structures, leveraging their relationships with the British to this end.

Legacies of Leadership

Perceptions of Collaboration: The two kings are sometimes perceived controversially, seen as either capitulating to colonial pressures or astutely navigating imperial dynamics for the welfare of their people.

Modernisation Effects: The infrastructural and educational advancements brought by the British had long-lasting effects on Barotseland and Bechuanaland, albeit with the attendant costs of colonial exploitation and cultural disruptions.

The Complexity of Collaboration

Motivations for Alliances: Lewanika and Khama’s decisions to collaborate were multifaceted, driven by geopolitical, economic, and cultural motivations.

Resistance to Imperialism: Their engagements with the British were nuanced forms of resistance to imperialism, reflecting a strategic choice rather than outright submission.

These detailed histories of Lewanika and Khama’s rule illustrate the varied responses to European imperialism in Africa. They highlight the careful balance African leaders attempted to strike between collaboration and resistance, often with the overarching goal of preserving their people’s welfare and autonomy.

FAQ

The relationships between Kings Lewanika and Khama with British colonial administrators evolved through phases of cooperation, tension, and renegotiation. Initially, both kings engaged with the British to secure protection and modernisation advantages. Over time, as the true intentions of the colonial administrators became clear, particularly with the BSAC’s exploitation of Barotseland’s resources, Lewanika’s relationship with the British grew strained. He frequently protested the company's actions, highlighting evolving tensions. In contrast, Khama maintained a relatively stable relationship by consistently negotiating and travelling to Britain to advocate for his people's rights, showing his adeptness in maintaining a positive, yet vigilant, diplomatic connection.

The long-term effects of Lewanika and Khama's collaborations with the British on the political landscape of Southern Africa were significant. Lewanika’s engagements with the British laid the groundwork for the eventual creation of Northern Rhodesia, later Zambia, with a legacy of mineral exploitation but also infrastructure development. Khama’s efforts resulted in the Bechuanaland Protectorate, which maintained a higher degree of political autonomy. This protectorate eventually became the modern nation of Botswana, renowned for its stable democracy and prudent management of mineral wealth. Both leaders' collaborations influenced colonial border demarcations and the political strategies of African leadership in the region, with their legacies evident in the post-colonial structures and policies of their respective countries.

The reactions of local populations in Barotseland and Bechuanaland to their leaders' decisions to collaborate with the British were complex and varied. In Barotseland, some factions viewed Lewanika’s treaties with suspicion, especially when the promised benefits, such as military support and development, were overshadowed by the BSAC’s exploitative actions. There was a sense of betrayal among certain groups. In Bechuanaland, Khama was largely successful in maintaining the support of his people. His clear stance on issues like alcohol prohibition and land rights resonated with the local population's values, reinforcing his position. However, it is important to note that not all reactions were uniform, and there were undoubtedly individuals and groups within both territories who opposed or questioned the collaborations to varying degrees.

Both Lewanika and Khama faced significant challenges to their strategies of collaboration with the British. Internally, they had to manage the dissatisfaction and dissent from local chiefs and factions who opposed yielding to British influence and questioned the concessions granted in various treaties. Externally, the most pressing challenges came from other colonial competitors, such as the Portuguese and the Boers, who had their own imperialist ambitions in the region. Additionally, the British South Africa Company’s (BSAC) own agenda in Barotseland posed a constant challenge to Lewanika, as their exploitative practices often contravened the initial spirit of the agreements made. Khama had to navigate the complex and often conflicting interests of British colonial administrators who could be capricious and not always supportive of his protectorate’s autonomy.

The British approach towards Bechuanaland and Barotseland reflected the broader strategies of indirect and direct rule within their imperial policy. In Bechuanaland, the British exercised a form of indirect rule, which allowed more local autonomy and limited interference in internal affairs, primarily due to King Khama III's successful negotiations. Barotseland, however, came under the British South Africa Company's (BSAC) administration, which represented a more direct form of control. The BSAC sought to exploit the region's natural resources and imposed more stringent administrative structures, which led to a significant reduction in local sovereignty compared to the protectorate status of Bechuanaland.

Practice Questions

Lewanika's diplomatic strategies displayed a nuanced understanding of the political landscape of colonial Africa. By entering into treaties with the British, he managed to keep other colonial powers at bay, thus maintaining a level of autonomy for Barotseland. However, the effectiveness of these strategies was compromised by the BSAC's manipulation of treaty terms, which eventually led to Lewanika's loss of control over mineral concessions and a reduction in Barotseland's sovereignty. Despite this, Lewanika succeeded in preserving his kingdom's cultural integrity and avoiding direct colonial administration, illustrating a degree of diplomatic success amid challenging imperial dynamics.

King Khama III sought collaboration with the British primarily to protect his kingdom from the expansionist policies of the Boers. His strategic alliance with the British was also motivated by a desire to modernise Bechuanaland and preserve its cultural and social structures. This collaboration resulted in Bechuanaland becoming a protectorate, which afforded it a measure of self-governance and prevented annexation by the South African Republic. Khama's adept diplomacy ensured that Bechuanaland retained control over its internal affairs, demonstrating that his collaboration significantly secured the kingdom's political status and safeguarded its territorial integrity.