IB Syllabus focus:

'The evolution of US–Japan relations leading up to WWII.

Key incidents that heightened tensions, including economic sanctions and political disputes.

The role of the US in influencing the international response to Japanese expansion.'

In the tumultuous years leading up to World War II, US-Japan relations experienced considerable tension and strain, underscored by a series of strategic decisions, economic embargoes, and political misunderstandings.

Evolution of US-Japan Relations Pre-WWII

Late 19th and Early 20th Century

Open Door Policy (1899-1900): Spearheaded by the US, this policy aimed to protect equal privileges among countries trading with China and to support China's territorial and administrative integrity. Japan's acceptance was lukewarm, as it had territorial ambitions in the region.

Gentlemen's Agreement (1907-1908): While not a formal treaty, the US and Japan reached an understanding to ease tensions regarding Japanese immigration to the US. The US agreed to not impose formal restrictions, while Japan promised to limit emigration.

Washington Naval Conference (1921-1922): To prevent an arms race after World War I, powers including the US and Japan convened to discuss naval limitations. The resulting treaties reflected cooperation but also underscored brewing distrust.

Japan’s Increasing Ambitions

1930s: Japan's quest for resources and territory, especially after the onset of the Great Depression, saw it engage in territorial expansions. The US, having economic and geopolitical interests in Asia, grew wary of Japan’s intentions.

Manchurian Incident (1931): Japan's seizure of Manchuria was viewed with alarm in Washington, signalling a clear divergence in the strategic objectives of the two nations.

Key Incidents Heightening Tensions

Economic Sanctions

1939 Embargo on Key Materials: Concerned about Japan's growing military assertiveness, the US embargoed the export of aviation motor fuels and high-grade scrap iron to Japan.

1940 Export Control Act: Strengthening its resolve, the US passed the Act, empowering the President to prohibit or curtail exports of military equipment and materials. By year-end, crucial materials like steel, iron, and aviation fuel were embargoed, dealing a blow to Japan's war endeavours.

1941 Oil Embargo: This sanction was particularly crippling. With the US supplying the lion’s share of Japan’s oil needs, this embargo, which also involved the British and Dutch, was a direct challenge to Japanese military campaigns.

Political Disputes

Japanese Aggression in China: The US adopted a stance of moral indignation against Japanese actions, especially after events like the Nanking Massacre. They extended Lend-Lease aid to China, assisting the Chinese resistance.

Panay Incident (1937): A Japanese bombing resulted in the sinking of the USS Panay, a neutral vessel. Japan swiftly apologised and compensated for the incident. However, the damage to the relationship was more lasting.

The U.S. river gunboat USS Panay sinks on the Yangtze after Japanese aircraft bombed it on 12 December 1937, an episode that sharpened U.S.–Japan tensions despite a formal apology and indemnity. The image underscores how single incidents at sea could reverberate diplomatically across the Pacific. Source

Immigration Issues: While the Gentlemen's Agreement attempted to address immigration tensions, underlying racial prejudices in the US persisted, leading to dissatisfaction in Japan.

US Influence on International Response to Japanese Expansion

Stimson Doctrine (1932)

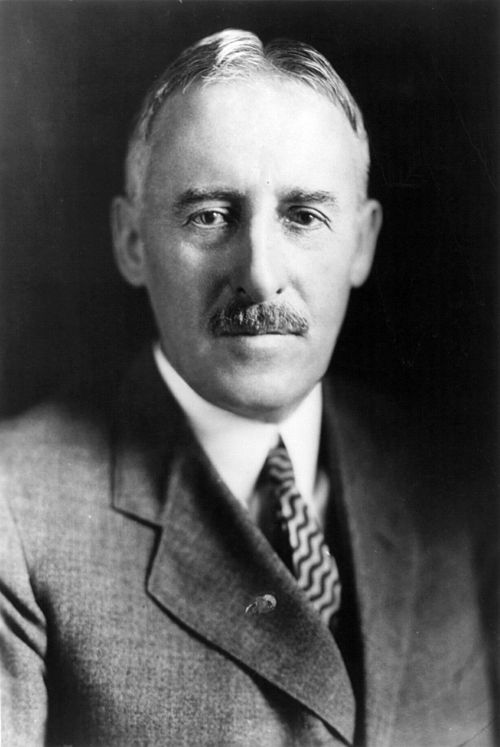

Following Japan's blatant territorial grab in Manchuria, Secretary of State, Henry L. Stimson, articulated the doctrine which denied recognition of territories acquired by force. This marked a clear, albeit non-military, rebuke of Japan's actions.

U.S. Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson, whose 1932 doctrine declared non-recognition of territorial changes achieved by force, signaling a firm—if nonmilitary—U.S. rebuke of Japanese expansion. The image includes no additional policy details beyond the syllabus scope. Source

Support for China

Monetary and Material Aid: Beyond moral support, the US extended tangible aid to China, assisting them in their struggle against Japanese aggression.

Flying Tigers: A volunteer group of American aviators went to China to fight against Japanese forces even before the US officially entered the war.

Cooperation with Allies

Multilateral Embargoes: The oil embargo was a product of trilateral collaboration between the US, Britain, and the Netherlands. This showcased a concerted effort to curtail Japanese expansion.

Intelligence Sharing: The US began sharing intelligence with other concerned powers, most notably Britain, concerning Japanese movements and intentions.

Naval Mobilisation

As tensions heightened, the US Pacific Fleet was shifted from its traditional base in San Diego to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, in 1940. This repositioning, closer to Japan's sphere of influence, was a clear signal of the US's commitment to counter any Japanese threat in the Pacific.

By the end of 1941, the intricate web of economic sanctions, political rebukes, and strategic posturing had painted both nations into a corner. For the US, Japanese aggression could not go unchecked. For Japan, the embargoes and political pressures threatened its very survival. The result was the infamous events of Pearl Harbor, plunging both nations into the cataclysm of World War II.

FAQ

The Japanese public, influenced by state-controlled media and nationalistic education, generally perceived the increasing tensions with the US as a clash between the East and West. Japan's actions in Asia were framed as efforts to liberate fellow Asian countries from Western imperialism. The economic sanctions imposed by the US were seen as attempts to stifle Japan's rightful rise as a global power. Patriotic fervour, combined with selective information dissemination, meant that the majority of the Japanese populace supported the government's expansionist policies and were prepared for potential conflict, believing in Japan's moral high ground and eventual victory.

The relocation of the US Pacific Fleet from San Diego to Pearl Harbor was a strategic move designed to deter and counter potential Japanese aggression. By shifting its major naval force closer to Japan's sphere of influence, the US was signalling its commitment to defending its interests in the Pacific. Pearl Harbor, due to its central location, allowed the fleet to respond more rapidly to potential threats in various parts of the Pacific. However, the move was also provocative, as Japan perceived it as a direct challenge and a manifestation of the growing American threat, further exacerbating the already strained relations between the two nations.

Japan viewed the US economic sanctions, especially the oil embargo, as an existential threat. Oil was vital for Japan's military and economic activities, and the embargo threatened its war efforts and industrial base. Consequently, Japan began to seek alternatives, increasing trade with the Dutch East Indies and exploring synthetic oil production. More drastically, Japan saw the need to secure resources by force, which partly led to its decision to expand further into Southeast Asia, specifically targeting oil-rich regions. The sanctions, instead of deterring Japan, pushed it to take aggressive actions that would ensure its access to vital resources, culminating in events such as the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Panay Incident in 1937, wherein Japanese aircraft attacked and sank the USS Panay, a neutral American gunboat patrolling the Yangtze River in China, was a significant event in the context of US-Japan relations. Although Japan quickly apologised and provided compensation, the incident underscored the unpredictability and volatility of Japan's military actions. For the American public, it was a stark reminder of the growing threat Japan posed in Asia, leading to heightened scepticism and mistrust towards Japan. While it didn't lead to direct military retaliation from the US, the Panay Incident did exacerbate already tense relations, pushing the two nations further along the path of confrontation.

Japan's expansionist drive in the 1930s was motivated by a combination of economic, strategic, and ideological factors. Economically, Japan sought to overcome its resource limitations, especially as the Great Depression affected its trade. Territories like Manchuria offered raw materials, like iron and coal, vital for Japan's industries. Strategically, securing territories could serve as buffers against potential threats and offer vantage points for further military manoeuvres. Ideologically, Japan was influenced by the concept of hakko ichiu, which proposed a Japan-led unification of Asia. This vision, combined with a sense of racial and cultural superiority, led Japan to believe it had a rightful place leading Asia against Western powers.

Practice Questions

The economic sanctions imposed by the US were a significant factor in the escalating tensions leading to World War II. From the embargo on aviation fuels and scrap iron in 1939 to the pivotal oil embargo in 1941, the US sought to curtail Japanese military endeavours and expansion in Asia. These sanctions, particularly the oil embargo, severely threatened Japan's war machine, making them feel cornered and compelling them to seek aggressive countermeasures. While other factors, such as political disputes and differing strategic objectives, played a role, economic sanctions were arguably the most immediate and potent catalyst for confrontation between the two nations.

The US significantly shaped the international reaction to Japan's expansionism in the 1930s. Through the Stimson Doctrine in 1932, the US firmly communicated its non-recognition of territories seized by force, setting a moral and political stance against Japan's actions in Manchuria. Additionally, by collaborating with allies like Britain and the Netherlands, the US formed a united front, best exemplified by the trilateral oil embargo. The embargo not only showcased the US's leadership in coordinating international policy but also its commitment to checking Japanese aggression. Lastly, the Lend-Lease aid to China further cemented the US's strategic and moral opposition to Japanese expansion, influencing other nations to follow suit.